Introduction: The Arc of a Christian Samurai’s Campaigns

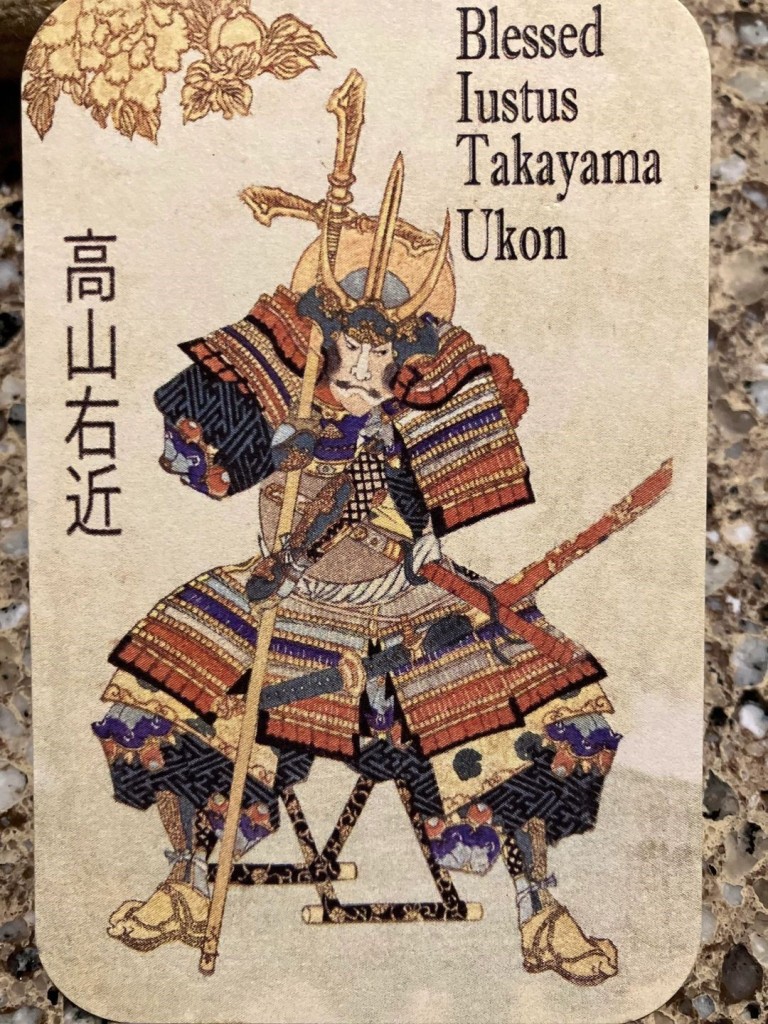

Blessed Justus (Justo) Takayama Ukon’s military life spanned the turbulent decades of the Sengoku age, from the collapse of his family’s Sawa stronghold in his childhood to his final service as a senior retainer of the Maeda clan on the eve of Sekigahara. His career mirrors the rise and fall of Japan’s warring states: early defeats that forged resilience, youthful victories that secured his lordship, celebrated triumphs at Yamazaki that cemented his reputation, and one bitter defeat at Shizugatake that cost him dearly in blood and kin.

Unlike many daimyo of his era, Ukon’s forces bore the distinctive banner of the Cross, reflecting the faith that shaped his decisions on and off the field. Yet his loyalty to Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and finally the Maeda lords shows that he remained a consummate military professional even as his Christianity drew suspicion and persecution.

What follows is a chronological account of eleven battles and campaigns in which Ukon took part — a narrative of valor, loss, and perseverance. From the ashes of Sawa to the walls of Daishōji, the battles trace the path of a samurai who fought under the shadow of the Cross until exile carried him from Japan to Manila, where he died a martyr in faith.

The Battles

❖ 1. Fall of Sawa Castle (c. 1565–1567)

As a child, Ukon witnessed his first battlefield disaster when his father, Takayama Tomoteru (高山友照), lost Sawa Castle (沢城) in Settsu during the turbulent wars between Matsunaga Hisahide and the Miyoshi clan. Though Ukon was not yet a combatant, this family defeat marked the beginning of his exposure to warfare and political instability.

Source: 高槻市史; Settsu annal entries on Sawa Castle.

❖ 2. Battle of Shiraikawara (白井河原の戦い, 1571)

In his adolescence, Ukon stood in the orbit of his father’s ally, Wada Koremasa (和田惟政). At the battle of Shiraikawara near Takatsuki, Wada was defeated and killed by the Araki–Nakagawa coalition. Ukon was too junior to command, but he saw how swiftly fortunes could change when a patron’s line was extinguished.

Source: “白井河原の戦い,” JP gazetteer; record of Wada Koremasa’s defeat.

❖ 3. Takatsuki Castle Struggle (高槻城, 1573)

By age 21, Ukon fought his first independent action. With his father, he challenged Wada Korenaga, son of the fallen Koremasa, in a skirmish of only a few dozen men. Both sides suffered wounds, but Wada was forced to withdraw, leaving Ukon in possession of Takatsuki Castle. This was Ukon’s first victory as a daimyo in his own right.

Source: 高槻市史; local history on Ukon’s expulsion of Wada Korenaga.

❖ 4. Battle of Yamazaki (山崎の戦い, 1582)

When Akechi Mitsuhide betrayed Oda Nobunaga at Honnōji, Ukon rallied under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. At Yamazaki, Ukon led the first detachment of fewer than 1,000 men. Contemporary sources say his troops, marked with crosses on their tunics, “so fired with the ardor of battle, and so confident with the help of God” that they slew more than 200 of Akechi’s nobles. Tokugawa Ieyasu is said to have remarked that “in Ukon’s hands 1,000 soldiers would be worth more than 10,000 in the hands of whosoever else.”

Source: James Murdoch, History of Japan II: 280–82; Johannes Laures, Justo Takayama Ukon.

❖ 5. Battle of Shizugatake (賤ヶ岳の戦い, 1583)

The next year, Ukon suffered his only recorded battlefield defeat. Hideyoshi placed him at Iwasaki-yama fort (岩崎山砦) to block Shibata Katsuie’s advance. In April 1583, Sakuma Morimasa attacked: Nakagawa Kiyohide was slain at nearby Ōiwa-yama, and Ukon was driven from Iwasaki-yama. Japanese sources note: “Nakagawa Kiyohide was killed, and Takayama Ukon abandoned the fort and escaped.” Ukon was wounded and lost many retainers, including kinsmen from the allied Kuroda and Ikeda families.

“Decimated” would be the incorrect word, as Lord Takayama, only 31, lost not only many of his own relatives, but lost the male kin of the Kuroda and Ikeda families, making the two families fade into history.

Takayama’s perfornance in this battle is debated by military historians to this day.

This “bitter defeat” left a lasting scar.

Source: 城郭放浪記 entry for Iwasaki-yama砦: “高山右近は砦を脱して逃げ延びた”

6. Komaki & Nagakute (小牧・長久手の戦い, 1584)

In the ensuing contest between Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, Ukon took part in skirmishes at Komaki, Gakuden, and Haguro. These engagements ended in stalemate; while Ukon’s presence is noted, no personal exploits or reverses are attributed to him in the chronicles.

Source: JP summaries of Komaki–Nagakute, 1584.

❖ 7. Shikoku Campaign (四国攻め, 1585)

When Hideyoshi turned to subdue Shikoku, Ukon accompanied him as part of his personal guard. No direct combat role for Ukon is recorded, but his presence at the side of the warlord underscored his growing trust.

Source: Shikoku campaign chronologies.

❖ 8. Kii Operations — Siege of Sawajō Castle (紀伊・沢城/佐和城, 1585–1586)

In the same years, Ukon commanded a largely Christian force in the suppression of the Negoro-shū warrior monks of Kii. His troops, again fighting under the banner of the Cross, besieged Sawajō Castle. The castle fell, strengthening Hideyoshi’s control in the Kansai.

Source: Regional Kii campaign summaries.

❖ 9. Kyūshū Campaign (九州征伐, 1587)

During Hideyoshi’s conquest of Kyūshū, Ukon again served as bodyguard. He accompanied Hideyoshi through Hakata, where the warlord issued the edict banning Christianity. For Ukon, the campaign marked a turning point: Victory in war, but personal loss in faith and fortune.

Source: Kyūshū campaign outlines; Hakata edict context.

❖ 10. Odawara Campaign — Siege of Hachigata (小田原征伐・鉢形城, 1590)

Ukon next appeared under the Maeda banner during the great campaign against the Hōjō. At Hachigata Castle, defended by Hōjō Ujikuni, the Maeda–Uesugi forces pressed a siege lasting more than a month. Ujikuni surrendered, opening the way to Odawara. Ukon fought as a guest general under Maeda Toshiie, marking the start of his Maeda service.

Source: 小田原征伐 campaign records; Hachigata Castle siege under Maeda & Uesugi.

❖ 11. Daishōji & Asainawate (大聖寺城・浅井畷, 1600)

Ukon’s last campaign came in 1600, as the Maeda clan aligned against Ishida Mitsunari’s forces in the Hokuriku. At Daishōji Castle, Yamaguchi Munenaga resisted with 1,200 men against Maeda Toshinaga’s 25,000. The castle fell; the Yamaguchi family committed seppuku. Days later, the armies clashed again at Asainawate, where the Maeda prevailed. Though Ukon is not named in the annal lines, he was by then one of the Maeda’s most seasoned generals.

Source: City of Kaga history on Daishōji; Asainawate battlefield notes.

Conclusion: The End of the Warrior’s Road

With the fall of Daishōji and the clash at Asainawate in 1600, Takayama Ukon’s battlefield career drew to a close. He had fought through the great contests of his age — Yamazaki, Shizugatake, Komaki–Nagakute, Odawara, and the Hokuriku prelude to Sekigahara — and had served three great powers in succession: Oda, Toyotomi, and Maeda. By then, he was no longer the youthful commander of Takatsuki but a seasoned general, respected even by adversaries for his courage and discipline.

Yet Ukon’s destiny did not lie in military glory. After Sekigahara, his Christian faith made him increasingly suspect under the Tokugawa. Stripped of his domains and pressed to abandon his beliefs, he refused. The man who had once borne the banner of the Cross into battle became instead a soldier of conscience, embracing exile rather than apostasy. His final campaign was not fought with sword and banner but with fidelity to Christ, leading him in 1614 onto the ship of exiles bound for Manila — and ultimately to the crown of martyrdom.

Thus, the story of Ukon’s eleven battles is not only the record of a samurai’s military service, but the prologue to his greater witness: a warrior who laid down the sword, and through suffering, gained victory in faith.

Dr. Ernesto A. de Pedro, PhD/History

Lead Promoter, Blessed Takayama Canonization Movement